Issues Surrounding the Release of Cellular Location Data

Through Spring and Summer 2018, a network of companies buying and selling access to the location of every customer of the four major carriers has been partially unveiled. Despite clear federal regulations governing receiving consent before providing access to customer data, some companies had rather loose consent policies. There have also been a few security vulnerabilities around access to this information.

Although it is not in the constitution, there is a long established legal history of a right to privacy, and in more modern times there has been a complicated mix of legal and regulatory decisions relating to the disclosure of customer information. A recent Supreme Court decision may have added a bit of clarity to the related legal environment.

This is an important issue for all Americans, because location data is unusually unique. A recent study has indicated that even with an anonymized dataset stripped of personally identifiable information, it may be possible to de-anonymize the dataset, given a few outside location points.

Sales of Cellular Location Data

In May 2018, the New York times wrote a story about a company called Securus that provides phone services to inmates (Valentino-DeVries 2018). One of the additional services they offer their customers is the ability to track the location of cellphones called by inmates, even if that phone has GPS disabled. This company had access to real-time location data for all of the major carriers (Whittaker 2018) in the United States, and some Canadian carriers, which would provide them access to most of the cellphones in this country. This valuable access to location data became even more worrisome when their lack of a process to verify law enforcement requests to track phones became apparent. Securus required users to upload a warrant or affidavit certifying that they had the legal authority to submit such a request. However, they were not performing any reviews of these documents, so this procedure was just a formality. A service this valuable with no oversight is ripe for abuse, as is evidenced by the former sheriff in Mississippi county MO who has been recently charged with abusing this service to track people without a valid warrant. (Valentino-DeVries 2018)

In a rather complex chain of transactions, Securus was purchasing their data from a company called 3Cinteractive, who was purchasing it from another company called LocationSmart. Carriers receive an overwhelming number of requests to confirm a customer’s location for things such as banks trying to prevent fraud, and roadside assistance services. Rather than deal with these requests themselves, the carriers rely on companies such as LocationSmart and 3Cinteractive to process and release customer data for them on a contract basis. The Customer is supposed to provide consent for this data release directly to the carrier, but it appears that the carriers have allowed the aggregators to handle this consent themselves, with little oversight into the effectiveness of their consent notification rules. There is, at this point, a chain of multiple companies involved in the request for the release of a customer’s data, and the actual data. Because of this, the opportunity for abuse of a customer’s personal data is omnipresent. (S. L. and J. Lynch 2018; Whittaker 2018).

Any company aggregating this much information on American and Canadian users would be a key target for security breaches, and both Securus and LocationSmart have had their share of issues. When the New York Times released the original story about Securus, a hacker came forward to tech blog Motherboard (Cox 2018) with proof that Securus’ network has been compromised. This anonymous hacker provided the blog with several internal company files, including a spreadsheet taken from a database called “police” containing over 2,800 usernames, email addresses, phone numbers, and passwords, some of which were unencrypted and accessible in cleartext (Cox 2018). Using the company’s forgotten password tool, the site was able to confirm that some pairs of usernames and emails on the spreadsheet were in fact stored on Securus’ network. A security breach of this scale provides a tremendous amount of access to personal location data, which could be a large problem for certain vulnerable populations.

In investigating this story, Robert Xiao, a security researcher from Carnegie Mellon University was investigating a demo tool LocationSmart has on their website. This tool allows potential customers to track the location of their own cellphone, requiring users to confirm via a text message that they would like to obtain the phone’s current location. However, the Application Programming Interface (API) providing the underlying data to this tool was doing so with no authentication or security whatsoever. Anyone with a little experience working with code or creating websites should be able to use this API to track any cellphone around the United States or Canada with no text message confirmation, or any kind of consent. After manually obtaining their permission, Xiao was able to track a few friends of his using this API, receiving results within a few seconds. In performing repeated searches on one user, he was even able to determine that one friend was in motion and could keep track of his path of travel by plugging coordinates into Google Maps. In this case, the vulnerability was disclosed by a security researcher who didn’t seem to have any ill intent with this data, but admittedly, he did not have much trouble finding it. One reason this is so problematic is that if he discovered it “almost by accident”, odds are he’s not the first one to do so. An insecure API providing access to data of this importance is a very compelling target for groups like private investigators, and intelligence agencies, so it is very likely that this vulnerability was in active use before Xiao publicized it (Krebs 2018).

It appears that both LocationSmart and Securus have been struggling with security problems, and have not been transparent about any unauthorized access to customer data. This is problematic, because the FCC regulations surrounding Customer Proprietary Network Information (CPNI) state that carriers should be required to notify a customer whenever a security breach results in that customer’s CPNI being disclosed to a third party without authorization. Further FCC regulations require carriers to maintain a record of all data that was disclosed or made available to third parties for at least a year. It’s not clear whether or not the carriers have been abiding by this rule, but the act of contracting out disclosures to third party companies could greatly complicate the carriers ability to store and maintain accurate disclosure records (S. L. and J. Lynch 2018).

Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon has been involved in getting answers on these disclosures and the related business arrangements. On May Ninth 2018, he sent a letter to the four major carriers, attempting to clarify legal requirements regarding customer information such as location, and pressing them for more specifics on the details of these data sharing agreements (Krebs 2018). Senator Wyden also sent a copy of this letter to the Federal Communications Commission, who confirmed that this issue has been referred to their enforcement division (Farivar 2018).

After Senator Wyden began pressing AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon for answers on the variety of customer location privacy issues, all four carriers have pledged to end business relationships with some combination of LocationSmart and the array of downstream companies who bought data from them. The four statements aren’t terribly detailed, and a complicated array of relationships like this will certainly take time to review and sever, but a pledge that they’re all focusing on the issue is a good start (Fung 2018; Statt 2018).

Potential Legal and Regulatory Issues

“Among personally identifiable information, location is considered as one of the most essential factors since the leak of location information can consequently lead to the disclosure of other sensitive private information such as occupations, hobbies, daily routines, and social relationships” (Hoang, Asano, and Yoshikawa 2017). It has been long established that the law recognizes a right to “be let alone”. This right covers the “extent his thoughts, sentiments, and emotions shall be communicated to others” (Warren and Brandeis 1890). Over the intervening 128 years, this right has been gradually updated as technology progresses and new problems arise. In recent years, this right has been interpreted by a variety of courts to cover different implementations of location tracking, either by GPS transmitter or the location of a cellphone in a carrier’s network. Details like court district, whether the location data is historical or real-time, in a private residence or in the public right-of-way, and the specifics of the technology used for tracking have all played a role in whether or not the location tracking is covered by the Fourth Amendment (Koppel 2009).

The government has long claimed that cellphone location data should be handled differently from a tactic such as using a GPS transmitter to track a person, due to the Third-Party Doctrine. This states that if the data in question was voluntarily given to a nongovernmental entity, it should not receive Fourth Amendment protection (A. C. and J. Lynch 2018). However, this theory was recently tested in the Supreme Court in Carpenter v. United States. In this case, the government had requested 127 days of his location records from MetroPCS without a warrant, in an attempt to tie him to a string of robberies in 2011 (“Carpenter v. United States” 2018).

In an amicus brief filed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (Crocker 2017), they argue that the underlying technology and use cases for telephone service have changed so much since the 1970s when the Third-Party Doctrine was first applied to telephony, that it isn’t appropriate to for location data generated by a cellphone. When this doctrine was created, a telephone could only generate a list of calls made and received, and was stationary in one location, so it did not have any useful data on a user’s location throughout the day. Cellphone data stored by the carriers today can provide an ongoing historical log of a person’s activities, movements and interpersonal communication, and could expose sensitive patterns of information, like repeated visits to therapists or other health providers. Although cellular carriers are technically nongovernmental entities, it’s difficult to make the argument that the use of a cellphone is optional, and there are ultimately only four carriers to choose from.

In June 2018, the Supreme Court ruled on Carpenter v United States, deciding that the fourth amendment protects cellphone location data with a few exceptions. The justices decided to take the unusual step of rejecting the Third-Party Doctrine. “In light of the deeply revealing nature of CSLI, its depth, breadth, and comprehensive reach, and the inescapable and automatic nature of its collection, the fact that such information is gathered by a third party does not make it any less deserving of Fourth Amendment protection” (Matsakis 2018). This was a narrow decision, focusing only on the act of requesting historical cellular location records for one particular user. However, the fact that the justices agreed there could be exceptions to the Third-party Doctrine should set a positive precedent for future cases based on similar technologies and situations.

Why is Location Privacy Special

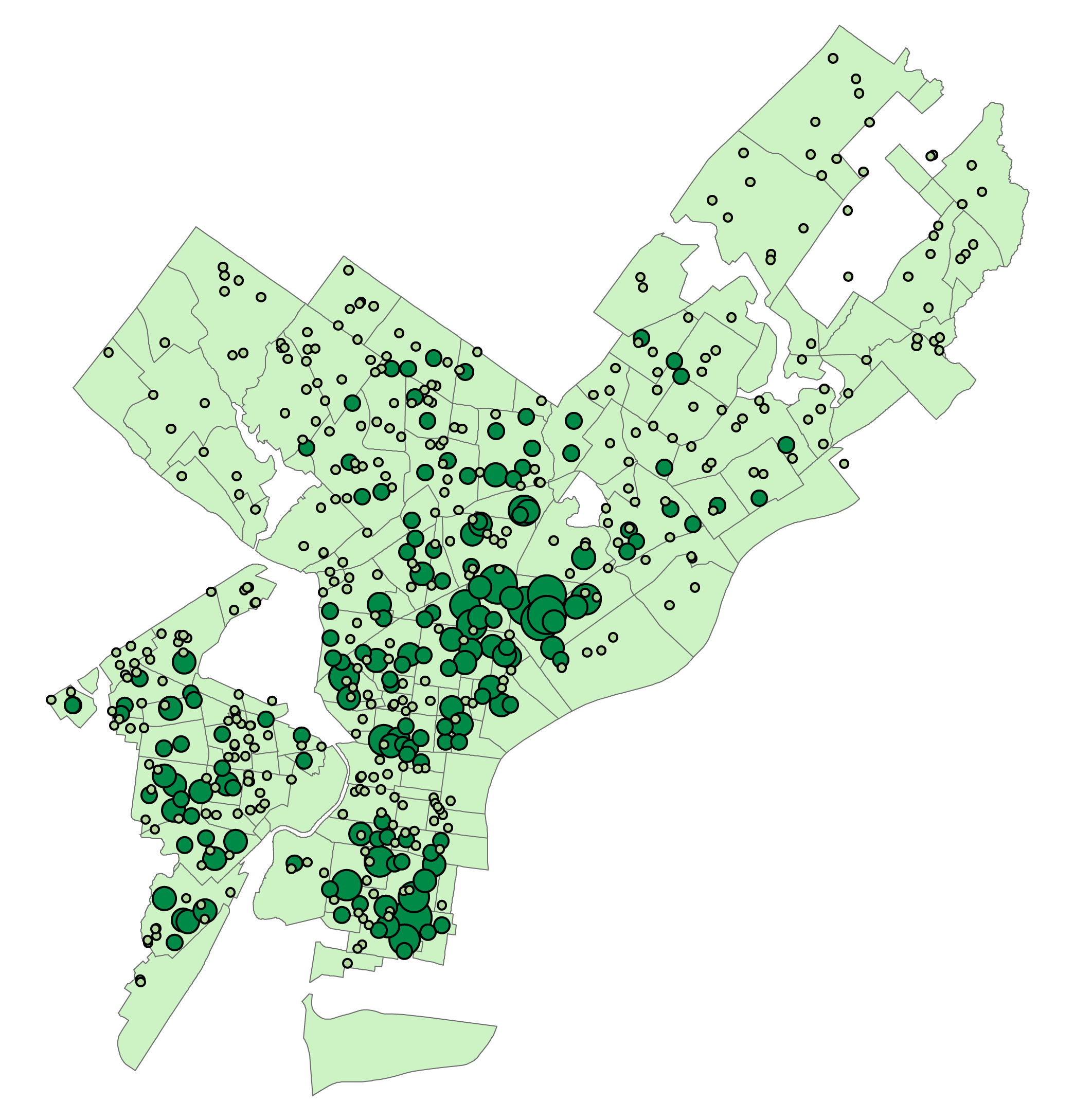

Ensuring the privacy of a user’s location is important, because human mobility data is especially unique. There are a prevalence of anonymized datasets available for research, and a few studies recently have shown that it is increasingly possible to uniquely identify users in these datasets. A study from MIT in 2012 analyzed an anonymized dataset of 1.5 million users moving through a cellular carrier’s network (mobility traces) for 15 months with the location specified hourly. With four randomly chosen points from this data, the researchers were able to uniquely identify 95% of the users, and two randomly chosen points are enough to identify more than 50% of the users. To start, a person’s home and office addresses are generally easily accessible. The other two of the four points could probably be obtained from check-ins on social networks or geotagged photos. This research makes a strong case that patterns of human travel are unique enough that the privacy of location data deserves special care. (Montjoye et al. 2013)

One tactic occasionally used by online services and social networks to safely display location data is decreasing the resolution of their data, intentionally displaying a less accurate version of the location in question (Duckham and Kulik 2005). After generating a highly significant model to estimate the uniqueness of a trace, the researchers at MIT used this model to predict the amount to which this method can protect a user’s privacy. The generated equation has an exponential effect, which means even very large decreases in the spatial or temporal resolution would result in relatively small decreases in the ability to identify users: “In fact, given four points, a two-fold decrease in spatial or temporal resolution makes it 9.3% less likely to identify an individual, while given ten points, the same two-fold decrease results in a reduction of only 6.2%” (Montjoye et al. 2013). They theorize that only a few more points would be sufficient to identify users in the less specific dataset. This indicates that decreasing the accuracy of the data might not provide enough of an increase in user privacy to be worth the corresponding large decrease in usefulness for a location-based service such as Foursquare or Facebook.

Conclusion

As we have seen, the four carriers’ willingness to share customer data with outside companies like LocationSmart in the name of profit has created a complex business environment surrounding what many believe should be private customer information. Securus Technologies, the subject of the original story on this ecosystem, had been buying customer data from 3Cinteractive, who bought it from LocationSmart, who bought it from AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon, among others. In addition to what has been reported so far, there could be dozens of other companies involved buying access, some of whom are providing potentially legitimate services, such as emergency roadside assistance, banks’ efforts to fight fraud, and companies monitoring remote workers.

There have been a few issues so far which may have resulted in customer location data being shared inappropriately. One issue is the policies of the myriad companies involved on what constitutes appropriate access to location data, and what the obligations are for notification and consent. This responsibility begins with the carriers, as they ultimately are the origin of the location data, and they are the ones whose customers are having their privacy violated. Secondarily, the security surrounding online access to this data is also suspect, as demonstrated by the incidents facing Securus and LocationSmart.

Because the underlying technologies in question are new and developing so rapidly, the surrounding legal and regulatory environment is still grappling with legal issues surrounding the current cellular communications environment. There have been a few notable court cases adding clarity to things like the application of the fourth amendment, and other privacy and surveillance issues. The legislative side of this, however, is still lacking, as the telecommunications legislation hasn’t had a major update since 1996.

This issue of user location privacy is important, because human mobility data is unusually unique. It has been shown that different attempts to anonymize or obfuscate location are not always sufficient to prevent people from being identified, given a sufficiently large dataset with a few outside data points. The Securus/LocationSmart story has generated a new level of interest around privacy issues, and hopefully some part of this attention will manifest in new consumer protections for cellular data.

Works Cited

“Carpenter v. United States.” 2018. Electronic Frontier Foundation. June 5, 2018. https://www.eff.org/cases/carpenter-v-united-states.

Cox, Joseph. 2018. “Hacker Breaches Securus, the Company That Helps Cops Track Phones Across the US.” Motherboard. May 16, 2018. https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/gykgv9/securus-phone-tracking-company-hacked.

Crocker, Andrew. 2017. “Amicus Brief for Carpenter.” Electronic Frontier Foundation. August 14, 2017. https://www.eff.org/document/amicus-brief-carpenter.

Duckham, Matt, and Lars Kulik. 2005. “A Formal Model of Obfuscation and Negotiation for Location Privacy.” In Pervasive Computing, 152–70. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/11428572_10.

Farivar, Cyrus. 2018. “FCC Investigates Site That Let Most US Mobile Phones’ Location Be Exposed.” Ars Technica. May 19, 2018. https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2018/05/fcc-investigates-site-that-let-most-us-mobile-phones-location-be-exposed/.

Fung, Brian. 2018. “Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile and Sprint Suspend Selling of Customer Location Data after Prison Officials Were Caught Misusing It.” Washington Post. June 19, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2018/06/19/verizon-will-suspend-sales-of-customer-location-data-after-a-prison-phone-company-was-caught-misusing-it/.

Hoang, N. P., Y. Asano, and M. Yoshikawa. 2017. “Your Neighbors Are My Spies: Location and Other Privacy Concerns in GLBT-Focused Location-Based Dating Applications.” In 2017 19th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), 851–60. https://doi.org/10.23919/ICACT.2017.7890236.

Koppel, Adam. 2009. “Warranting a Warrant: Fourth Amendment Concerns Raised by Law Enforcement’s Warrantless Use of GPS and Cellular Phone Tracking Note.” University of Miami Law Review 64: 1061–90.

Krebs, Brian. 2018. “Tracking Firm LocationSmart Leaked Location Data for Customers of All Major U.S. Mobile Carriers Without Consent in Real Time Via Its Web Site — Krebs on Security.” May 2018. https://krebsonsecurity.com/2018/05/tracking-firm-locationsmart-leaked-location-data-for-customers-of-all-major-u-s-mobile-carriers-in-real-time-via-its-web-site/.

Lynch, Andrew Crocker and Jennifer. 2018. “Victory! Supreme Court Says Fourth Amendment Applies to Cell Phone Tracking.” Electronic Frontier Foundation. June 22, 2018. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2018/06/victory-supreme-court-says-fourth-amendment-applies-cell-phone-tracking.

Lynch, Stephanie Lacambra and Jennifer. 2018. “Senator Wyden Demands Answers from Prison Phone Service Caught Sharing Cellphone Location Data.” Electronic Frontier Foundation. May 11, 2018. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2018/05/senator-wyden-calls-fcc-investigate-real-time-location-data-sharing-all-cellphone.

Matsakis, Louise. 2018. “The Supreme Court Just Greatly Strengthened Digital Privacy.” Wired, June 22, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/carpenter-v-united-states-supreme-court-digital-privacy/.

Montjoye, Yves-Alexandre de, César A. Hidalgo, Michel Verleysen, and Vincent D. Blondel. 2013. “Unique in the Crowd: The Privacy Bounds of Human Mobility.” Scientific Reports 3 (March): 1376. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01376.

Statt, Nick. 2018. “AT&T and Sprint to Follow Verizon in Ending Its Sale of User Location Data to Third-Party Brokers.” The Verge. June 19, 2018. https://www.theverge.com/2018/6/19/17479490/att-follows-verizon-user-location-data-sale-brokers.

Valentino-DeVries, Jennifer. 2018. “Service Meant to Monitor Inmates’ Calls Could Track You, Too.” The New York Times, May 11, 2018, sec. Technology. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/10/technology/cellphone-tracking-law-enforcement.html.

Warren, Samuel D., and Louis D. Brandeis. 1890. “The Right to Privacy.” Harvard Law Review 4 (5): 193–220. https://doi.org/10.2307/1321160.

Whittaker, Zack. 2018. “US Cell Carriers Are Selling Access to Your Real-Time Phone Location Data.” ZDNet. May 14, 2018. https://www.zdnet.com/article/us-cell-carriers-selling-access-to-real-time-location-data/.